*Cover Image by Jozef Mikulcik from Pixabay *

One of the concepts in JavaScript that beginners find hard to wrap their heads around is prototypes, especially for Programmers coming from a class-based programming language.

You might ask “Doesn’t modern JavaScript have the class keyword?”

Yes, it does, but it’s just ‘sugar’ over prototypes, and understanding how prototypes work can save you a lot of stress when debugging JavaScript code.

JavaScript is weird but understanding it makes it less weird in my opinion (if you trust that my opinion matters :) )

Start with Why

Classes and Prototypes are different but they have a common idea: They allow us to reuse code. A class defines a ‘blueprint’ for creating an object that contains the fields defined in the class.

With this ‘blueprint’, we can create as many objects as we need. As we shall see shortly, although prototypes work differently, they also allow us to reuse code.

Objects and their members

Consider the following object

var song = {

title: "Bed of Stones",

artiste: "Asa",

getDescription : () => {

return "Best song on earth"

}

}

The members of this object are title, artiste, and getDescription.

Members that reference a function are called methods (getDescription in this example) while the others are considered as the object’s properties. However, it’s common to refer to all members as properties.

Prototypes

A prototype is an object serving as a base object for another object.

What does that even mean?

Remember that object contains members, so if we interpret song.title as asking for the title member from the song object, then a prototype is another object we can ask a member from if the object we are dealing with does not have that member.

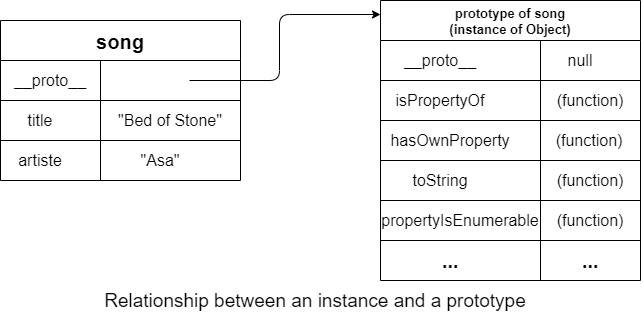

An object is tied to its prototype via an internal property which most browsers expose as __proto__.

By default, every time a new instance of a built-in type such as Array or Object is created, these instances automatically have an instance of the global Object as their prototype.

var song = {

title: "Bed of Stones",

artiste: "Asa"

}

console.log(typeof song.__proto__) // prints "object"

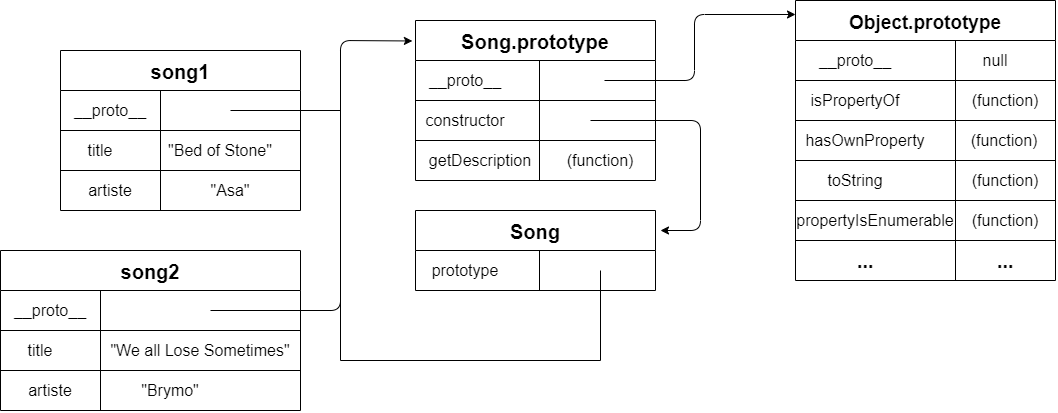

This prototype object contains members too, some of them are represented in the diagram below:

When we write,

When we write,

song.toString()

The JavaScript engine will first check the members of the song object for toString, when it doesn’t find it, it then checks the prototype of the song object. In this case, it finds the toString property there.

Types of Object Members

From our previous section, it means that an object can have two types of members:

- Instance members a.k.a its own members

- Prototype members

JavaScript provides ways by which we can differentiate both. For example, we can write

console.log(song.hasOwnProperty("title")) //prints true

console.log(song.hasOwnProperty("artiste")) //prints true

console.log(song.hasOwnProperty("toString")) //prints false

The hasOwnProperty(fieldName) asks the JavaScript engine if fieldName is an instance member of the object in question.

On the other hand, the in operator in JavaScript checks for both the instance and prototype members

console.log("title" in song) //true

console.log("artiste" in song) //true

console.log("toString" in song) //true

Quiz: How are we able to access hasOwnProperty on the song object even though it’s not defined on it?

Prototype Chains

As mentioned earlier, by default all objects in JavaScript have their prototype from the global Object. We say they are instances of Object.

JavaScript provides different ways by which we can set the prototype of an object ourselves. It is not recommended to assign a new object to the __proto__ property directly. It’s not well supported by all browsers.

Object.create()

Consider the following code snippet:

var song = {

title: "Bed of Stones",

artiste: "Asa"

}

// creates a new object which prototype is 'song'

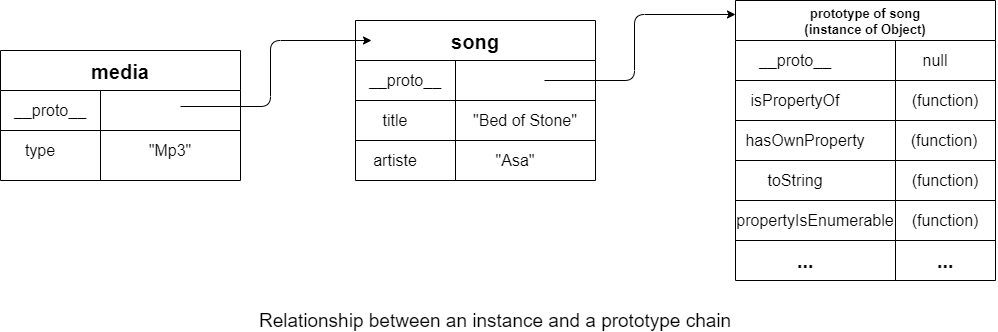

var media = Object.create(song)

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(media)) // [object Object] { artiste: "Asa", title: "Bed of Stones" }

Object.create(song) will create a new object and set its prototype to the song object. Instead of reading an object’s prototype via the __proto__ property, we can also use Object.getPrototypeOf as the example illustrates.

You can pass another object to Object.create to add specific instance properties to the object being created. For example:

// creates a new object that has this structure { type: "Mp3"} and whose prototype is the song object

var media = Object.create(song, { type: {value: "Mp3" } })

console.log(media.type) // prints "Mp3"

console.log(media.title) // prints "Bed of Stones"

Constructor Functions

Another way by which you can create an object with a custom prototype is by using Constructor Functions. Strictly, any function can be used as a constructor but by convention, constructor function names start with a capital letter.

To create an instance of a constructor function, you use the new keyword with the function invocation, for example:

function Bar() {}

var bar = new Bar() // creates a new object

When the new keyword is used, JavaScript assigns the keyword this implicitly to the new object being created. So we can use this to refer to the object being created:

function Bar() {

this.name = "bar"

}

var bar = new Bar()

console.log(bar.name) // "bar"

The Constructor Function prototype Property

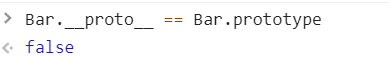

Every function in JavaScript has the special property prototype.

You might ask, since functions are objects too, is the prototype property the same as the __proto__?

Yeah. The object pointed to by the

Yeah. The object pointed to by the prototype property of a Constructor Function is not the function’s prototype. So what is it?

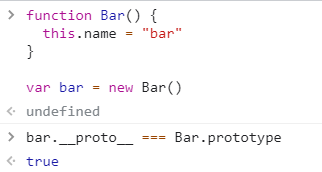

Remember I mentioned that a Constructor Function can be used to create a new object…and set the new object’s prototype? The new object’s prototype is the object pointed to by the Constructor Function prototype property.

Let me rephrase this in another way.

- Every function has a

prototypeproperty - You can create an object (a.k.a instance) of the function by using the

newkeyword - The object’s prototype is set to the constructor function’s

prototypeproperty

Let me wrap this up with the following code snippet:

function Song(title, artiste) {

this.title = title

this.artiste = artiste

}

Song.prototype.getDescription = function() {

return this.title + " by " + this.artiste

}

var song1 = new Song("Bed of Stones", "Asa")

var song2 = new Song("We all Lose Sometimes", "Brymo")

console.log(song1.title) // "Bed of Stones"

console.log(song2.artiste) // "Brymo"

console.log(song2.getDescription()) // "We all Lose Sometimes by Brymo"

song1 and song2 share the same prototype chain. Notice that Song.prototype has a property constructor, this is created by JavaScript to point to the constructor function, in this case, Song.

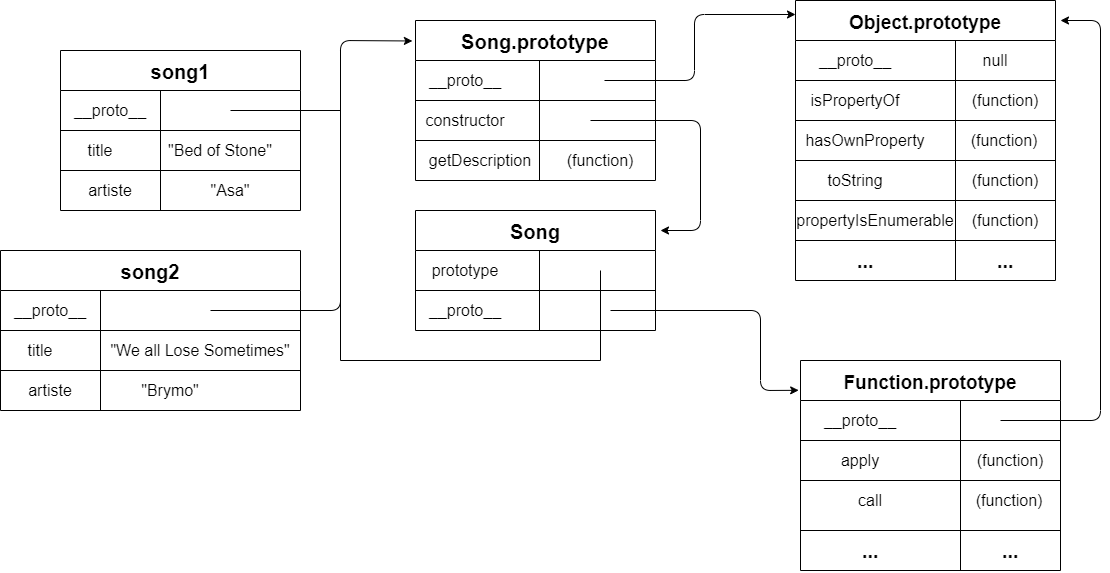

The diagram above has been simplified, Song itself has a __proto__ property, the diagram below shows it:

Conclusion

Wow. You have gotten this far. Nice nice :) We have discussed all I think is necessary in order to understand and better debug JavaScript programs with regards to prototypes.

If you find any error, kindly point it out.

Happy Coding

Bonus: instanceof vs typeof

Suppose we have

function Bar() {

this.name = "bar"

}

var bar = new Bar()

When we write

console.log(bar instanceof Bar) // prints true

bar instanceof Bar means that we are asking the JavaScript engine the question,

Does

Bar.prototypeexist anywhere in the prototype chain ofbar?

The answer in this case is yes (true).

instanceof operator tests whether the prototype property of the Constructor Function appears in the prototype chain of the object.

Can you guess what this will print?

console.log(bar instanceof Object)

Again the answer is true because Object.prototype exists in the prototype chain of bar

typeof operator

The typeof operator returns a string indicating the type of the operand. The string returned can be any of "symbol", "bigint", "number", "string", "boolean", "object", "function" or “undefined”

Example:

typeof 12 === 'number'; // returns true